‘The ball is mainly in the court of the government and financial institutions, not the citizens.’

Bas Kolen on his research into the consequences of flooding and extreme precipitation for insurance companies

19 January 2026

Solidarity and efficiency are essential values for both Dutch water managers and insurers. Still, according to Bas, the use of flood risk data in the financial sector requires an entirely different approach than in water management. He warns that overestimating risks can lead to unnecessarily high costs.

What follows are excerpts from Bas Kolen’s inaugural lecture. Since September last year, he has held the chair in Enterprise Risk Management at the Actuarial Science and Mathematical Finance research group at the Amsterdam School of Economics.

The world is constantly changing

Climate is, of course, always subject to change, but the speed of change is now much greater. Insurers' claims figures show that climate events and damage are on the rise.

Hurricane Katrina was the largest insured loss event in the past 45 years, with damages amounting to approximately €172 billion, but not everything in America is bigger. In 2006, my colleagues and I developed the Worst-Case Flood scenario for various parts of the Netherlands. Converted to current price levels, the damage for the coastal scenario would then be a maximum of €194 billion. This only concerns the damage caused by flooding in the Netherlands. Damage caused by wind and damage in neighbouring countries that were also affected in 1953, for example, has not yet been included.

Quantitative risk analysis is indispensable to deliberative democracy [[[[Sunstein 2002. Risk and reason: safety, law, and the environment. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.]]: a society in which decisions are made through consultation, transparency, and argument. It is about providing insight into considerations, not about automatically minimizing costs. In this speech, I will discuss the relationship between water management and insurance, limiting myself to the economic risk. The risk may increase due to climate change and spatial, demographic, and economic developments, and it may decrease due to mitigation and adaptation. The costs are borne by society through taxes and insurance premiums.

It is tempting and too simplistic to view the world as stable, with climate change as the spoilsport. The world is constantly changing; climate risks have always existed, and, over the centuries, choices have been made about how we should relate to them.

In a journey through time, I distinguish between physical and organizational changes and shifts in perception regarding the associated questions about risk acceptance.

The perception of safety has undergone significant changes over time. In the past, floods were seen as an act of nature or even an act of God. The 1953 flood disaster was described by the Minister of Transport and Water Management as “Who can turn the hand of the Lord?”. After 1953, the enormous investment in the Delta Works led to the perception that the battle against the water had been won. Today, in the Netherlands (through the Delta Programme, NLAAA, and studies by planning agencies and advisory bodies) and in many parts of the world, floods are recognised as a social issue, with discussions focusing on the distribution of responsibilities, compensation for damage, and preventive measures.

Over time, institutions have also been established to manage risks, such as ministries that formulate policy and set requirements for flood defences or housing construction. However, I will focus on:

- Water boards, focused on flood prevention;

- Insurers, focused on compensation for damage.

Water boards and insurers have their own cultures, with blind spots and protocols of their own.

A history spanning centuries

In what is now the Rhineland, the first mention of heemraden (flood protection officers) dates back to 1255, to organise joint flood protection. In other words, prevention: reducing the risk of flooding and inundation. The water boards collect taxes to be able to implement their measures, in addition to other tasks such as the (much more costly) purification of water. In recent decades and in the decades to come, the likelihood of a dike breach in the Netherlands will continue to decrease, thereby reducing the risk. Yes, climate change is happening, which could increase the likelihood, but all the investments in flood defenses are actually reducing the risk.

So while the actual risk of dyke breaches in the Netherlands is decreasing, the feeling of insecurity is increasing.

Currently, the water boards also advise on spatial planning. This is where ambitions and responsibilities clash (think of Zuidplan, Rijnenburg, Limburg), where it is easy to “spend other people’s money” under the banner of safety. A joint normative framework for all authorities seems desirable to me.

Insurers are older than the water boards. In Babylonia, insurance schemes were already in place centuries before the Common Era. The Dutch East India Company utilised insurance solutions in the Netherlands to spread its risks. In the 17th century, insurance as we know it today emerged.

Blind spot

In recent decades, financial products have become increasingly complex, and the Dutch economy has also become more dependent on the financial sector. As a result, shocks such as floods can have major and sometimes unexpected effects on the entire economy. To this, one could also add the confidence in the Netherlands in risk management through prevention.

In a stress test for the Netherlands, the DNB and the IMF investigated the consequences for the financial sector of dyke breaches and catastrophic floods, comparable to those of 1953. At the macro level, the effects appear to be limited; the Netherlands will not go under. However, the question is whether this is also the case at the level of individual companies, and what the possible chain effects are. This remains a blind spot in the research, which does not foster confidence.

The risk paradox

To date, the insurance premium for households due to precipitation has been distributed almost equally among policyholders, indicating a solidarity-based approach rather than an individual one. In its recent analysis of flood risks, the CPB also explicitly makes this choice: should risks and adaptation measures be invested in collectively (through solidarity) or individually (e.g., at the household level)? Would an individual approach not lead to undesirable side effects? Insight into the risks is therefore necessary, so let’s do the maths!

If insurance premiums are increased based on this argument, it seems to me that society will not accept this, and rightly so.

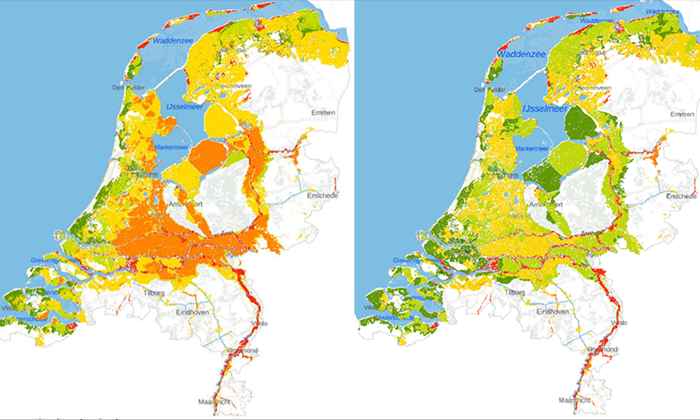

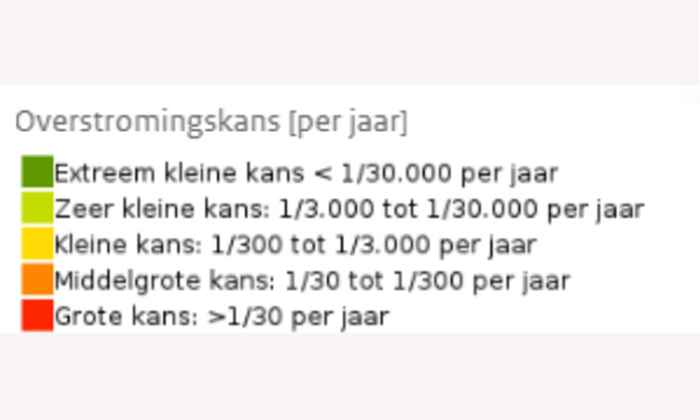

In addition, I note that a phenomenon from the world of safety science now also applies: the risk paradox. While the actual risk of dyke breaches in the Netherlands is decreasing, the feeling of insecurity is increasing. The available information is suddenly being interpreted differently and in a much more ominous way. This is the case with terrorism, for example, and also applies to climate change in the Netherlands. Some people in the Netherlands discuss climate refugees relocating from flood-prone areas, despite the actual risk of flooding having decreased significantly in recent decades. If insurance premiums are increased based on this argument, it seems to me that society will not accept this, and rightly so.

Language matters

Authorities often use words such as “safe” and “climate-resilient” in the context of risk management. However, these terms are problematic because they create the illusion that flooding can be ruled out, which is not the case. This is relevant because awareness of water risks is essential to prevent damage and promote personal resilience. The OECD already pointed out a false sense of security to the Netherlands in 2014, prompting the launch of the website overstroomik.nl in 2015, where people can find information about the consequences of flooding.

Living in a delta, river valley or on a mountainside is never without risks.

Language is important. Let’s therefore stop using terms such as 'safe' and 'climate-robust,' however appealing they may sound. In this speech, I will refer to 'acceptable risk', or simply 'risk'. Living in a delta, river valley or on a mountainside is never without risk. The precautionary principle does not apply here, as it is and was impossible to eliminate all risks. The question is therefore which risks “we” accept and how “we” distribute the costs of these risks and measures. It is therefore a matter of choice.

Get started!

So, “we” are insured against climate risks in the Netherlands and worldwide. Extreme weather events have occurred in the past and will continue to occur in the future, and then there are floods. “We” have reduced the risks, and it seems sensible to continue doing so. Cooperation between the government, insurers, and financial institutions is necessary. Based on the principles of efficiency and solidarity, I have shown that the ball is mainly in the court of the government and financial institutions, not in the hands of the citizen. Costs are shared through taxes, and insurance costs are spread across all policyholders. In my view, the collective approach is a great asset, and “we” must therefore be wary of side effects whereby ‘we’ make the risks of flooding very clear and place them on the individual.

Insight into the risks and how they are constructed is, of course, necessary in all cases. I have taken you through the challenges and knowledge gaps that exist and how I hope to contribute from my chair. The basis is therefore to assess uncertainties and understand risk and damage modeling, in order to analyze climate effects and a range of policy options. I have shown how the perspective of the water manager and the insurer contributes to improving the quality of the risk analysis. I have also shown where the challenges lie. There is plenty to do, so let's get started!