We can restrain ourselves: Why history matters in the climate crisis

Peter van Dam on the history of meatless eating in the Netherlands

16 December 2024

For Peter van Dam, essential in light of the climate crisis is the question of how people manage to impose restrictions on themselves. By way of illustration, he gave an interesting overview of the history of meatless eating in the Netherlands in his inaugural lecture on 13 December 2024. And that history goes back surprisingly far! Whereas meat had previously been a luxury product, its consumption began to increase substantially during the 19th century. Between 1852 and 1901, for instance, the average consumption of veal and beef per inhabitant of Amsterdam doubled from around 7.9 to 15.5 kilos a year, and with it, so did the resistance to eating meat.

What follows is part of the inaugural lecture of Peter van Dam, appointed professor of Dutch history in the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Amsterdam.

Start of the vegetarian movement in the Netherlands: 1894

A vegetarian movement emerged at the breaking point of the previous two centuries. A number of pioneers united in 1894 in the Dutch Vegetarians Union. In their view, eating meat was unethical and unhealthy. Unethical, because people did not need to kill animals. Unhealthy, because vegetarians regarded meat as a stimulant food that should be avoided for that reason. Many of them therefore also did not consume alcohol, salt and spices. They cut back on drinking coffee and tea. Did this rejection of tropical products also reflect an aversion to the colonial consumer society that permeated their environment?

Many of them therefore also did not consume alcohol, salt and spices. They cut back on drinking coffee and tea.

The small group of vegetarians tried to convince people of the vegetarian lifestyle with publications on science and ethics. Soon, a more practical initiative also took off. In

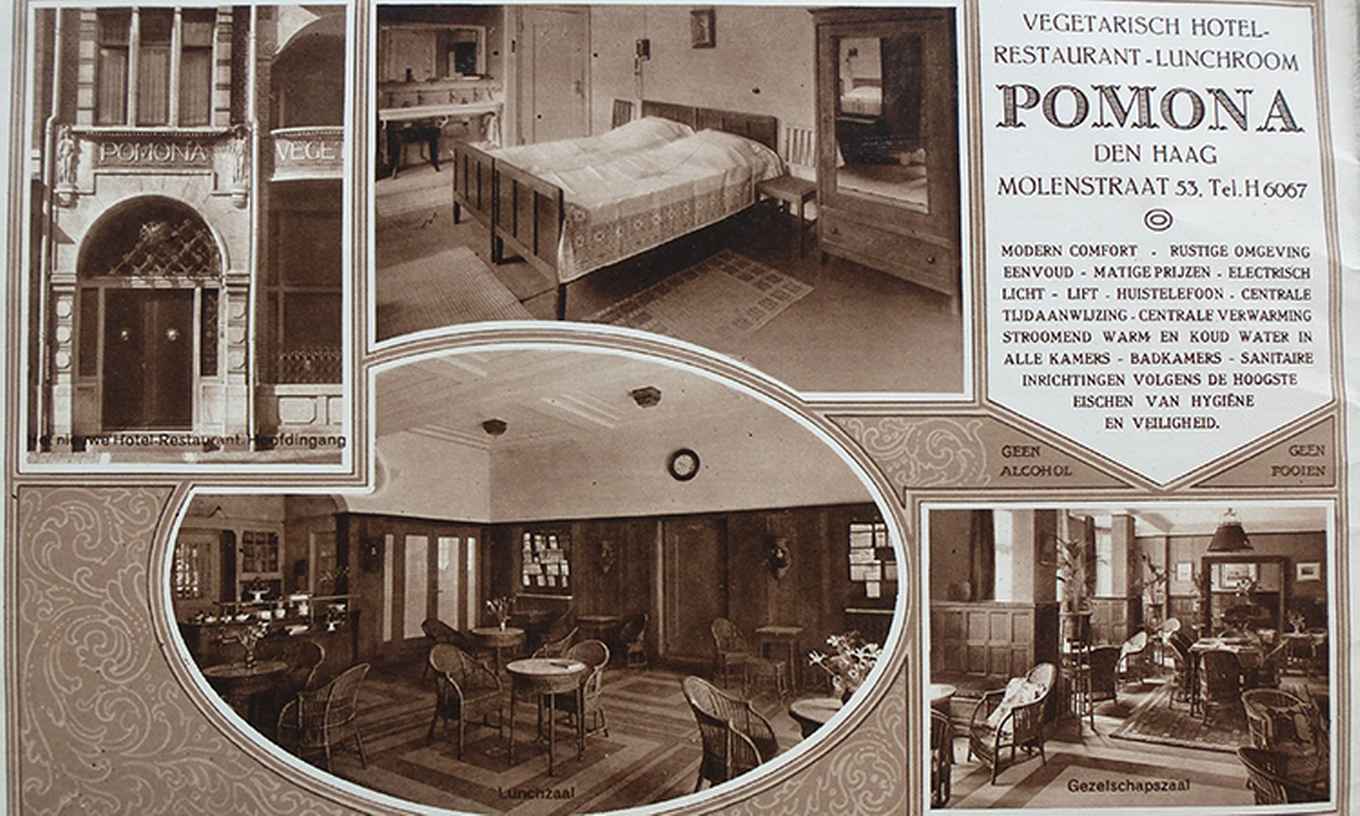

1898 in The Hague, Elisabeth Valk-Heynsdeijk opened a vegetarian restaurant, Hotel Restaurant Pomona. Valk-Heynsdeijk's emphasis on ‘the taste with which the little room was furnished, the cleanliness and tidiness and the practical arrangement’ makes it clear that these vegetarians were oriented towards bourgeois circles, people who could afford a visit to a proper hotel restaurant.

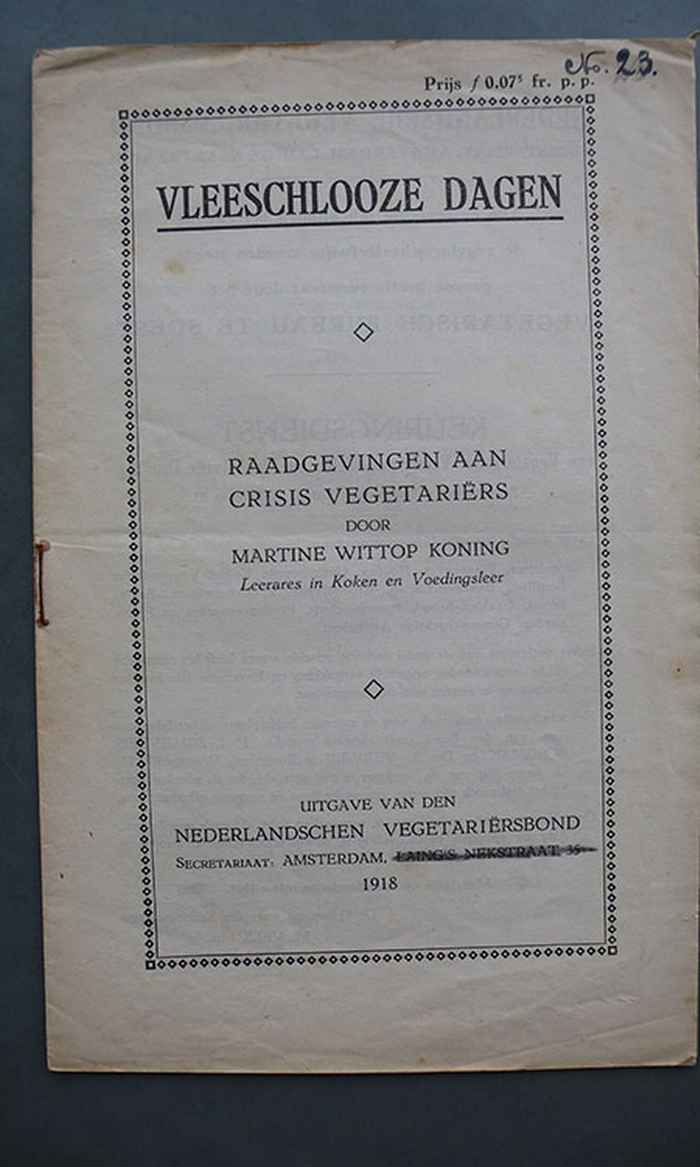

Beyond the small circle of principled vegetarians, scarcity remained important. For example, when food shortages arose during the First World War. For these ‘crisis vegetarians’, the famous household education pioneer and cookbook author Martine Wittop Koning wrote a cookbook in 1918. In it, the vegetarian-in-need learned how to cook a ‘vegetarian philosopher’ – not a call for cannibalism, but a dish of leftovers with fried onion and a dash of milk.

How World War II diminished the distance

The vegetarians were part of an international movement. We do not fully understand the movement until we trace these transnational intertwines. In 1947, vegetarians from 12 countries celebrated the centenary of the British Vegetarian Union together. Like their contemporaries, they were forced to redefine their place in the post-war world. The world war had reduced the everyday distance between vegetarians and others. Many people had eaten meatless out of necessity. Conversely, some vegetarians had to renounce their principles to survive.

International relations changed dramatically, and so did meatless eating. At the 1947 congress, participants sent greetings to Indian independence fighter and well-known vegetarian Mahatma Gandhi. Thus, they took sides with people in colonised territories who claimed their independence. In the vegetarian movement, contacts with supporters from these countries, especially India, began to play an important role after 1945.

Thus, meatless food took on a different face after 1945, internationally and locally. Chic restaurants like Pomona disappeared. Vegetarian meals were more often available in mainstream restaurants. Even before the war, the Vegetarian Union published tips for hoteliers in the Dutch East Indies and the Netherlands who had vegetarian guests. The

The Union also issued lists of restaurants where vegetarians could sit down with confidence. This shows that this was not the case everywhere, but also that vegetarians became a less exclusive group.

International solidarity and the world food issue

Besides health and animal rights, solidarity was also an important motive. In the crisis years of the interwar period some argued for phasing out meat production, given the many people who could not find work in the 1930s. Growing livestock feed came at the expense of producing food that people could eat for themselves. Agriculture – and certainly horticulture – provided much more work than livestock farming. So eating less meat was a way to ensure people could make a living.

During the international vegetarian congresses after World War II, these kinds of considerations recurred, this time in the light of expected global population growth. If this continued, a meatless diet could make a significant contribution to the so-called ‘world food problem’ by not wasting agricultural land to produce feed for animals.

From the 1960s, concerns about the food people consumed on a daily basis increased. A globalised food industry brought more and more processed food onto the market and increased the distance between producer and consumer. In agriculture, mechanisation, breeding, fertilisers and pesticides pushed production to unprecedented levels. The Dutch agricultural sector played a prominent role in this. At the same time, criticism grew of the uneven international distribution of the new prosperity.

Health, animal rights, environment and climate

At the time of another international vegetarian congress it was easy to see that the reasons for reducing meat consumption kept shifting. In 1994, vegetarians from all over the world came to The Hague to celebrate the centenary of the Dutch Vegetarian Union. Health was now less in the spotlight. Philosopher Peter Singer spoke about animal rights. Other speakers denounced the environmental impact of the meat industry and put environmental pollution explicitly on the agenda. Climate change had been a major topic at the international conferences in nearby Noordwijk in 1989 and at the ‘Earth Summit’ in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, but among vegetarians, little was heard about it in 1994.

By analysing the attempts to eat less meat, we can see how motives such as health, animal rights, environmental concerns and solidarity shaped the pursuit of sustainability.

More research is needed on the phenomenon of self-limitation

We can also discern a second dimension: the question of when people restricted themselves; in times of crisis and scarcity, but also in everyday life. This dimension of the history of sustainability deserves more attention.

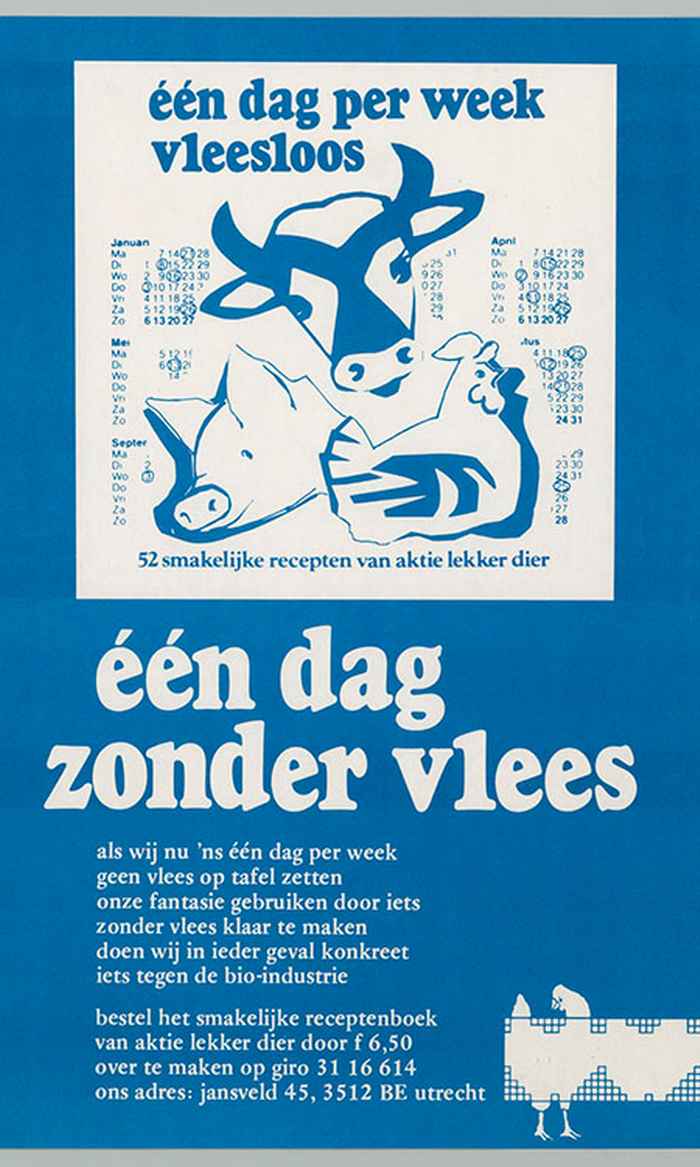

The Vegetarian Union had discovered the ‘flexitarian’ in the 1980s and used it, among other things, to encourage catering companies to put more meatless dishes on the menu for this target group. The stakes shifted from completely switching to a vegetarian diet to ‘a day without meat’. The rise of the flexitarian has had a major impact on reducing meat consumption over the past 30 years.

In 2020, the Dutch Central Bureau of Statistics deemed it undisputed that eating meat had ‘a major impact on the climate and the environment’. Against that background, CBS researchers welcomed the fact that a growing group of Dutch people ate meat at most four days a week. The group of flexitarians is now so accepted that the Voedingscentrum published its own cookbook for this target group, Today Vegetarian. Besides questions about healthy eating, the climate was also discussed. For instance, a recipe such as ‘Capuchin salad with tomatoes and rocket’ was touted as a ‘climate whopper’ because it produced ‘over a third less CO2 emissions than an average hot meal.

Not the 'oil slick model' but the process of coalition building

How could a marginal initiative like that of vegetarians around 1900 grow into an influential phenomenon? We usually view such social changes in a kind of 'oil slick model'. An initiative starts with a small group of people and then – if successful – manages to reach more and more people.

In my opinion, we can better capture the process from a small initiative to a broader movement as a process of successful coalition building. A group reaches other individuals and groups, but they fit the initiative into their own context. Consider the rise of the flexitarian. Concerns about global inequality, environment and climate changed the desire to eat less meat. After all, those who started eating less meat for these reasons did not have to renounce meat altogether.

In a process of coalition building, an initiative constantly changes its character. Broad coalitions often bring together a range of motives. To remain recognisable, common activities are crucial. Coalitions often gain size and influence thanks to low-threshold actions that people can easily join - such as the ‘day without meat’. In the coming years, I want to use new research to further analyse the different phases in broadening a social initiative and the tactics deployed at different times.

The rise of the flexitarian has had a major impact on reducing meat consumption over the past 30 years.

There are also lessons to be learned from the counter movement

The flip side of these histories is equally important. Many initiatives to change the world remained marginal. Low-level actions sometimes add a lot of water to the wine. And attempts to change something can lead to a countermovement. In recent years, for instance, we have seen increasing resistance to measures to further restrict meat consumption. The lobby for the traditional meatball and industrial agriculture shows how closely consumer culture, industrial agriculture and welfare policy have become intertwined.

We can also learn a lot from such cases about resistance, pitfalls and competing views and activities. This is where the influence of economic interests becomes visible and the tactics companies have used to secure their business models. Resistances and alternatives show the expectations with which citizens and politicians face each other in the welfare state. The laborious scaling up of sustainability initiatives also questions the limited willingness to regulate the global market.

A grounded history thus connects contemporary questions about sustainability with the past. Using environmental history and an interweaving perspective, we can start landing. Around earthly issues like what we eat, we don't have to pit local and global against each other. The critical connection with the past provides new insights into how initiatives can grow and what roles everyday activities, diverse motives and the time factor play in it.